Director honoured by Royal Society of Chemistry

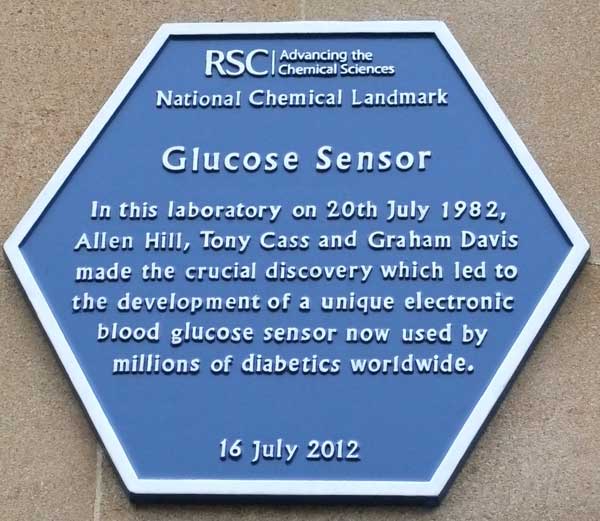

One of Bio Nano Consulting’s founding directors, Professor Tony Cass of the Imperial College Chemistry Department, was among three scientists honoured recently by the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) for their contributions to diabetes monitoring. Specifically, the team that created a new type of sensor allowing diabetics to easily and accurately monitor their blood sugar levels was awarded a National Chemical Landmark blue plaque on July 16 at the University of Oxford’s Department of Chemistry. Dr Robert Parker, Chief Executive of the Royal Society of Chemistry, unveiled the plaque that recognises the work by Allen Hill, Graham Davis, and Professor Cass.

In the 1980s, the trio developed a new technique that enabled a range of proteins to be investigated using electrochemistry, paving the way for a new type of monitoring device. Previously glucose monitoring had been carried out using ‘colorimetric’ methods, where a drop of blood was applied to a strip that changed colour to indicate the concentration of glucose in the blood. But these methods required a large droplet of blood and were not very accurate. The new approach started with work into how proteins gain or lose electrons when linked in to an electrical circuit. Studying such electrochemical behaviour was difficult as the proteins tended to stick to the electrodes, creating a build-up which prevented a current from flowing. Allen and undergraduate student Mark Eddowes developed a way of protecting the electrodes by binding another molecule to them that did not interfere with the current. The protein could now pick up an electron from one electrode via the surface bound molecule and lose it at the other electrode, thereby allowing a huge range of proteins to be investigated electrochemically for the first time.

In 1982 Allen, working with Tony Cass and Graham Davis, overcame a major drawback of the new method when applied to enzymes that used oxygen – the latter interfered with the electron transfer processes. They used ferrocene as a carrier of the electrons, thereby creating a much more stable system. By using the enzyme which breaks down glucose (glucose oxidase) as the protein component in the device they were able to construct a new type of sensor. Glucose oxidase reacts with any glucose in a sample, giving up electrons that are passed on to the electrode via the oxidised ferrocene: the larger the concentration of glucose the larger the current measured by the device. Importantly, the new device needed just the tiniest pinprick of blood, would work with blood straight from the body, and could measure glucose levels much more accurately than colorimetric methods.

The innovation led to the formation of a new company (Medisense) and the new glucose monitoring device finally went on sale in 1989. The greatest legacy of the work is that the many variants of the original Oxford-developed glucose monitor are used by people with diabetes all over the world today.

Commenting on the original breakthrough and how the technology has developed since Prof Allen said: “The initial reaction was a mixture of excitement and frustration; the former because we realised how useful the system we had discovered could be, frustration because it took a very long time parading our wares before one company after another before we were fortunate to meet Mr Zwanziger (the initial investor). Now the devices have developed enormously but they are still related to what we found in the 80s.”

Dr Parker added: “The work carried out here at Oxford’s Department of Chemistry has been instrumental at providing enormous comfort to the three million diabetics sufferers in the UK, and many more millions worldwide, who can today safely and accurately monitor their blood sugar levels. It is a privilege to be here today to pay tribute to the team behind that ground-breaking research by awarding them the Royal Society of Chemistry’s National Chemical Landmark plaque.”